Fidel Castro, Cuban Revolutionary Who Defied U.S., Dies at 90

Mr. Castro brought the Cold War to

the Western Hemisphere, bedeviled 11

American presidents and briefly

pushed the world to the brink of

nuclear war.

Fidel Castro, the fiery apostle of

revolution who brought the Cold War

to the Western Hemisphere in 1959

and then defied the United States for

nearly half a century as Cuba’s

maximum leader, bedeviling 11

American presidents and briefly

pushing the world to the brink of

nuclear war, died Friday. He was 90.

His death was announced by Cuban

state television.

In declining health for several years,

Mr. Castro had orchestrated what he

hoped would be the continuation of

his Communist revolution, stepping

aside in 2006 when he was felled by a

serious illness. He provisionally ceded

much of his power to his younger

brother Raúl, now 85, and two years

later formally resigned as president.

Raúl Castro, who had fought alongside

Fidel Castro from the earliest days of

the insurrection and remained

minister of defense and his brother’s

closest confidant, has ruled Cuba since

then, although he has told that the

Cuban people he intends to resign in

2018.

Fidel Castro had held on to power

longer than any other living national

leader except Queen Elizabeth II. He

became a towering international

figure whose importance in the 20th

century far exceeded what might have

been expected from the head of state

of a Caribbean island nation of 11

million people.

He dominated his country with

strength and symbolism from the day

he triumphantly entered Havana on

Jan. 8, 1959, and completed his

overthrow of Fulgencio Batista by

delivering his first major speech in the

capital before tens of thousands of

admirers at the vanquished dictator’s

military headquarters.

A spotlight shone on him as he

swaggered and spoke with passion

until dawn. Finally, white doves were

released to signal Cuba’s new peace.

When one landed on Mr. Castro,

perching on a shoulder, the crowd

erupted, chanting: “Fidel! Fidel!” To

the war-weary Cubans gathered there

and those watching on television, it

was an electrifying sign that their

young, bearded guerrilla leader was

destined to be their savior.

Most people in the crowd had no idea

what Mr. Castro planned for Cuba. A

master of image and myth, Mr. Castro

believed himself to be the messiah of

his fatherland, an indispensable force

with authority from on high to control

Cuba and its people.

He wielded power like a tyrant,

controlling every aspect of the island’s

existence. He was Cuba’s “Máximo

Lider.” From atop a Cuban Army tank,

he directed his country’s defense at

the Bay of Pigs. Countless details fell

to him, from selecting the color of

uniforms that Cuban soldiers wore in

Angola to overseeing a program to

produce a superbreed of milk cows.

He personally set the goals for sugar

harvests. He personally sent countless

men to prison.

ADVERTISEMENT

But it was more than repression and

fear that kept him and his totalitarian

government in power for so long. He

had both admirers and detractors in

Cuba and around the world. Some saw

him as a ruthless despot who trampled

rights and freedoms; many others

hailed him as the crowds did that first

night, as a revolutionary hero for the

ages.

Even when he fell ill and was

hospitalized with diverticulitis in the

summer of 2006, giving up most of his

powers for the first time, Mr. Castro

tried to dictate the details of his own

medical care and orchestrate the

continuation of his Communist

revolution, engaging a plan as old as

the revolution itself.

By handing power to his brother, Mr.

Castro once more raised the ire of his

enemies in Washington. United States

officials condemned the transition,

saying it prolonged a dictatorship and

again denied the long-suffering Cuban

people a chance to control their own

lives.

But in December 2014, President

Obama used his executive powers to

dial down the decades of antagonism

between Washington and Havana by

moving to exchange prisoners and

normalize diplomatic relations

between the two countries, a deal

worked out with the help of Pope

Francis and after 18 months of secret

talks between representatives of both

governments.

Though increasingly frail and rarely

seen in public, Mr. Castro even then

made clear his enduring mistrust of

the United States. A few days after Mr.

Obama’s highly publicized visit to

Cuba in 2016 — the first by a sitting

American president in 88 years — Mr.

Castro penned a cranky response

denigrating Mr. Obama’s overtures of

peace and insisting that Cuba did not

need anything the United States was

offering.

To many, Fidel Castro was a self-

obsessed zealot whose belief in his

own destiny was unshakable, a

chameleon whose economic and

political colors were determined more

by pragmatism than by doctrine. But

in his chest beat the heart of a true

rebel. “Fidel Castro,” said Henry M.

Wriston , the president of the Council

on Foreign Relations in the 1950s and

early ’60s, “was everything a

revolutionary should be.”

Mr. Castro was perhaps the most

important leader to emerge from

Latin America since the wars of

independence in the early 19th

century. He was decidedly the most

influential shaper of Cuban history

since his own hero, José Martí ,

struggled for Cuban independence in

the late 19th century. Mr. Castro’s

revolution transformed Cuban society

and had a longer-lasting impact

throughout the region than that of any

other 20th-century Latin American

insurrection, with the possible

exception of the 1910 Mexican

Revolution .

His legacy in Cuba and elsewhere has

been a mixed record of social progress

and abject poverty, of racial equality

and political persecution, of medical

advances and a degree of misery

comparable to the conditions that

existed in Cuba when he entered

Havana as a victorious guerrilla

commander in 1959.

That image made him a symbol of

revolution throughout the world and

an inspiration to many imitators.

Hugo Chávez of Venezuela considered

Mr. Castro his ideological godfather.

Subcommander Marcos began a revolt

in the mountains of southern Mexico

in 1994, using many of the same

tactics. Even Mr. Castro’s spotty

performance as an aging autocrat in

charge of a foundering economy could

not undermine his image.

But beyond anything else, it was Mr.

Castro’s obsession with the United

States, and America’s obsession with

him, that shaped his rule. After he

embraced Communism, Washington

portrayed him as a devil and a tyrant

and repeatedly tried to remove him

from power through an ill-fated

invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, an

economic embargo that has lasted

decades, assassination plots and even

bizarre plans to undercut his prestige

by making his beard fall out.

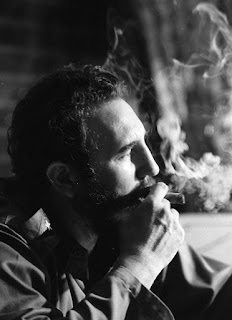

Mr. Castro’s defiance of American

power made him a beacon of

resistance in Latin America and

elsewhere, and his bushy beard, long

Cuban cigar and green fatigues

became universal symbols of

rebellion.

Mr. Castro’s understanding of the

power of images, especially on

television, helped him retain the

loyalty of many Cubans even during

the harshest periods of deprivation

and isolation when he routinely

blamed America and its embargo for

many of Cuba’s ills. And his mastery

of words in thousands of speeches,

often lasting hours, imbued many

Cubans with his own hatred of the

United States by keeping them on

constant watch for an invasion —

military, economic or ideological —

from the north.

Over many years Mr. Castro gave

hundreds of interviews and retained

the ability to twist the most

compromising question to his favor.

In a 1985 interview in Playboy

magazine, he was asked how he would

respond to President Ronald Reagan’s

description of him as a ruthless

military dictator. “Let’s think about

your question,” Mr. Castro said, toying

with his interviewer. “If being a

dictator means governing by decree,

then you might use that argument to

accuse the pope of being a dictator.”

He turned the question back on

Reagan: “If his power includes

something as monstrously

undemocratic as the ability to order a

thermonuclear war, I ask you, who

then is more of a dictator, the

president of the United States or I?”

ADVERTISEMENT

After leading his guerrillas against a

repressive Cuban dictator, Mr. Castro,

in his early 30s, aligned Cuba with the

Soviet Union and used Cuban troops

to support revolution in Africa and

throughout Latin America.

His willingness to allow the Soviets to

build missile-launching sites in Cuba

led to a harrowing diplomatic standoff

between the United States and the

Soviet Union in the fall of 1962, one

that could have escalated into a

nuclear exchange. The world

remained tense until the

confrontation was defused 13 days

after it began, and the launching pads

were dismantled.

With the dissolution of the Soviet

Union in 1991, Mr. Castro faced one of

his biggest challenges: surviving

without huge Communist subsidies. He

defied predictions of his political

demise. When threatened, he fanned

antagonism toward the United States.

And when the Cuban economy neared

collapse, he legalized the United States

dollar , which he had railed against

since the 1950s, only to ban dollars

again a few years later when the

economy stabilized.

Mr. Castro continued to taunt

American presidents for a half-

century, frustrating all of

Washington’s attempts to contain him.

After nearly five decades as a pariah

of the West, even when his once

booming voice had withered to an old

man’s whisper and his beard had

turned gray, he remained defiant.

He often told interviewers that he

identified with Don Quixote, and like

Quixote he struggled against threats

both real and imagined, preparing for

decades, for example, for another

invasion that never came. As the

leaders of every other nation of the

hemisphere gathered in Quebec City in

April 2001 for the third Summit of the

Americas , an uninvited Mr. Castro,

then 74, fumed in Havana, presiding

over ceremonies commemorating the

embarrassing defeat of C.I.A.-backed

exiles at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. True

to character, he portrayed his

exclusion as a sign of strength,

declaring that Cuba “is the only

country in the world that does not

need to trade with the United States.”

Personal Powers

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz was born

on Aug. 13, 1926 — 1927 in some

reports — in what was then the

eastern Cuban province of Oriente, the

son of a plantation owner, Ángel

Castro, and one of his maids, Lina Ruz

González , who became his second wife

and had seven children. The father

was a Spaniard who had arrived in

Cuba under mysterious circumstances.

One account, supported by Mr. Castro

himself, was that his father had agreed

to take the place of a Spanish

aristocrat who had been drafted into

the Spanish Army in the late 19th

century to fight against Cuban

independence and American

hegemony.

Other versions suggest that Ángel

Castro went penniless to Cuba but

eventually established a plantation

and did business with the despised,

American-owned United Fruit

Company. By the time Fidel was a

youngster, his father was a major

landholder.

Fidel was a boisterous young student

who was sent away to study with the

Jesuits at the Colegio de Dolores in

Santiago de Cuba and later to the

Colegio de Belén, an exclusive Jesuit

high school in Havana. Cuban lore has

it that he was headstrong and

fanatical even as a boy. In one

account, Fidel was said to have

bicycled head-on into a wall to make a

point to his friends about the strength

of his will.

In another often-repeated tale, young

Fidel and his class were led on a

mountain hike by a priest. The priest

slipped in a fast-moving stream and

was in danger of drowning until Fidel

pulled him to shore, then both knelt in

prayers of thanks for their good

fortune.

A sense of destiny accompanied Mr.

Castro as he entered the University of

Havana’s law school in 1945 and

almost immediately immersed himself

in radical politics. He took part in an

invasion of the Dominican Republic

that unsuccessfully tried to oust the

dictator Rafael Trujillo. He became

increasingly obsessed with Cuban

politics and led student protests and

demonstrations even when he was not

enrolled in the university.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mr. Castro’s university days earned

him the image of rabble-rouser and

seemed to support the view that he

had had Communist leanings all along.

But in an interview in 1981, quoted in

Tad Szulc’s 1986 biography, “ Fidel ,”

Mr. Castro said that he had flirted

with Communist ideas but did not join

the party.

“I had entered into contact with

Marxist literature,” Mr. Castro said.

“At that time, there were some

Communist students at the University

of Havana, and I had friendly

relations with them, but I was not in

the Socialist Youth, I was not a

militant in the Communist Party.”

He acknowledged that radical

philosophy had influenced his

character: “I was then acquiring a

revolutionary conscience; I was active;

I struggled, but let us say I was an

independent fighter.”

After receiving his law degree, Mr.

Castro briefly represented the poor,

often bartering his services for food.

In 1952, he ran for Congress as a

candidate for the opposition Orthodox

Party. But the election was scuttled

because of a coup staged by Mr.

Batista.

Mr. Castro’s initial response to the

Batista government was to challenge it

with a legal appeal, claiming that Mr.

Batista’s actions had violated the

Constitution. Even as a symbolic act,

the attempt was futile.

His core group of radical students

gained followers, and on July 26,

1953 , Mr. Castro led them in an attack

on the Moncada barracks in Santiago

de Cuba. Many of the rebels were

killed. The others were captured, as

were Mr. Castro and his brother Raúl.

At his trial, Mr. Castro defended the

attack. Mr. Batista had issued an

order not to discuss the proceedings,

but six Cuban journalists who had

been allowed in the courtroom

recorded Mr. Castro’s defense.

“As for me, I know that jail will be as

hard as it has ever been for anyone,

filled with threats, with vileness and

cowardly brutality,” Mr. Castro

declared . “I do not fear this, as I do

not fear the fury of the miserable

tyrant who snuffed out the life of 70

brothers of mine. Condemn me, it does

not matter. History will absolve me.”

Mr. Castro was sentenced to 15 years

in prison. Mr. Batista then made what

turned out to be a huge strategic

error. Believing that the rebels’ energy

had been spent, and under pressure

from civic leaders to show that he was

not a dictator, he released Mr. Castro

and his followers in an amnesty after

the 1954 presidential election.

Mr. Castro went into exile in Mexico,

where he plotted his return to Cuba.

He tried to buy a used American PT

boat to carry his band to Cuba, but the

deal fell through. Then he caught sight

of a beat-up 61-foot wooden yacht

named Granma, once owned by an

American who lived in Mexico City.

The Granma remains on display in

Havana, encased in glass.

Man of the Mountains

During Mr. Castro’s long rule, his

character and image underwent

several transformations, beginning

with his days as a revolutionary in the

Sierra Maestra of eastern Cuba. After

arriving on the coast in the

overloaded yacht with Che Guevara

and 80 of their comrades in December

1956, Mr. Castro took on the role of

freedom fighter. He engaged in a

campaign of harassment and guerrilla

warfare that infuriated Mr. Batista,

who had seized power in a 1952

garrison revolt, ending a brief period

of democracy.

Although his soldiers and weapons

vastly outnumbered Mr. Castro’s, Mr.

Batista grew fearful of the young

guerrilla’s mesmerizing oratory. He

ordered government troops not to rest

until they had killed Mr. Castro, and

the army frequently reported that it

had done so. Newspapers around the

world reported his death in the

December 1956 landing. But three

months later, Mr. Castro was

interviewed for a series of articles that

would revive his movement and thus

change history.

The escapade began when Castro

loyalists contacted a correspondent

and editorial writer for The New York

Times, Herbert L. Matthews, and

arranged for him to interview Mr.

Castro. A few Castro supporters took

Mr. Matthews into the mountains

disguised as a wealthy American

planter.

ADVERTISEMENT

Drawing on his reporting, Mr.

Matthews wrote sympathetically of

both the man and his movement,

describing Mr. Castro, then 30, parting

the jungle leaves and striding into a

clearing for the interview.

“This was quite a man — a powerful

six-footer, olive-skinned, full-faced,

with a straggly beard,” Mr. Matthews

wrote.

The three articles, which began in The

Times on Sunday, Feb. 24, 1957,

presented a Castro that Americans

could root for. “The personality of the

man is overpowering,” Mr. Matthews

wrote. “Here was an educated,

dedicated fanatic, a man of ideals, of

courage and of remarkable qualities of

leadership.”

The articles repeated Mr. Castro’s

assertions that Cuba’s future was

anything but a Communist state. “He

has strong ideas of liberty, democracy,

social justice, the need to restore the

Constitution, to hold elections,” Mr.

Matthews wrote. When asked about

the United States, Mr. Castro replied,

“You can be sure we have no

animosity toward the United States

and the American people.”

The Cuban government denounced Mr.

Matthews and called the articles

fabrications. But the news that he had

survived the landing breathed life into

Mr. Castro’s movement. His small

band of irregulars skirmished with

government troops, and each

encounter increased their support in

Cuba and around the world, even

though other insurgent forces in the

cities were also fighting to overthrow

the Batista government.

It was the symbolic strength of his

movement, not the armaments under

Mr. Castro’s control, that

overwhelmed the government. By the

time Mr. Batista fled from a darkened

Havana airport just after midnight on

New Year’s Day 1959, Mr. Castro was

already a legend. Competing

opposition groups were unable to

seize power.

Events over the next few months

became the catalyst for another

transformation in Mr. Castro’s public

image. More than 500 Batista-era

officials were brought before courts-

martial and special tribunals,

summarily convicted and shot to

death. The grainy black-and-white

images of the executions broadcast on

American television horrified viewers.

Mr. Castro defended the executions as

necessary to solidify the revolution.

He complained that the United States

had raised not a whimper when Mr.

Batista had tortured and executed

thousands of opponents.

But to wary observers in the United

States, the executions were a signal

that Mr. Castro was not the

democratic savior he had seemed. In

May 1959, he began confiscating

privately owned agricultural land,

including land owned by Americans ,

openly provoking the United States

government.

In the spring of 1960, Mr. Castro

ordered American and British

refineries in Cuba to accept oil from

the Soviet Union . Under pressure from

Congress, President Dwight D.

Eisenhower cut the American sugar

quota from Cuba, forcing Mr. Castro

to look for new markets. He turned to

the Soviet Union for economic aid and

political support. Thus began a half-

century of American antagonism

toward Cuba.

Finally, in 1961, he gave the United

States 48 hours to reduce the staff of

its embassy in Havana to 18 from 60.

A frustrated Eisenhower broke off

diplomatic relations with Cuba and

closed the embassy on the Havana

seacoast. The diplomatic stalemate

lasted until 2015, when embassies

were finally reopened in both Havana

and Washington.

During his two years in the

mountains, Mr. Castro had sketched a

social revolution whose aim, at least

on the surface, seemed to be to restore

the democracy that Mr. Batista’s coup

had stifled. Mr. Castro promised free

elections and vowed to end American

domination of the economy and the

working-class oppression that he said

it had caused.

Despite having a law degree, Mr.

Castro had no real experience in

economics or government. Beyond

improving education and reducing

Cuba’s dependence on sugar and the

United States, his revolution began

without a clear sense of the new

society he planned, except that it

would be different from what had

existed under Mr. Batista.

At the time, Cuba was a playground

for rich American tourists and

gangsters where glaring disparities of

wealth persisted, although the country

was one of the most economically

advanced in the Caribbean.

After taking power in 1959, Mr. Castro

put together a cabinet of moderates,

but it did not last long. He named

Felipe Pazos, an economist, president

of the Banco Nacional de Cuba, Cuba’s

central bank. But when Mr. Pazos

openly criticized Mr. Castro’s growing

tolerance of Communists and his

failure to restore democracy, he was

dismissed. In place of Mr. Pazos, Mr.

Castro named Che Guevara, an

Argentine doctor who knew nothing

about monetary policy but whose

revolutionary credentials were

unquestioned.

Opposition to the Castro government

began to grow in Cuba, leading

peasants and anti-Communist

insurgents to take up arms against it.

The Escambray Revolt , as it was called,

lasted from 1959 to 1965, when it was

crushed by Mr. Castro’s army.

As the first waves of Cuban exiles

arrived in Miami and northern New

Jersey after the revolution, many were

intent on overthrowing the man they

had once supported. Their number

would eventually total a million, many

from what had been, proportionately,

the largest middle class in Latin

America.

The Central Intelligence Agency helped

train an exile army to retake Cuba by

force. The army was to make a

beachhead at the Bay of Pigs, a remote

spot on Cuba’s southern coast, and

instigate a popular insurrection.

Mr. Szulc, then a correspondent for

The Times, had picked up information

about the invasion, and had written

an article about it. But The Times, at

the request of the Kennedy

administration, withheld some of what

Mr. Szulc had found, including

information that an attack was

imminent. Specific references to the

C.I.A. were also omitted.

Ten days later, on April 17, 1961,

1,500 Cuban fighters landed at the Bay

of Pigs. Mr. Castro was waiting for

them. The invasion was badly planned

and by all accounts doomed. Most of

the invaders were either captured or

killed. Promised American air support

never arrived. The historian Theodore

Draper called the botched operation “a

perfect failure,” and the invasion

aroused a distrust of the United States

that Mr. Castro exploited for political

gain for the rest of his life.

Declaration or Deception?

The C.I.A., fighting the Cold War, had

acted out of worries about Mr.

Castro’s increasingly open Communist

connections. As he consolidated

power, even some of his most faithful

supporters grew concerned. One

break had taken place as early as

1959. Huber Matos , who had fought

alongside Mr. Castro in the Sierra

Maestra, resigned as military governor

of Camagüey Province to protest the

Communists’ growing influence as

well as the appointment of Raúl

Castro, whose Communist sympathies

were well known, as commander of

Cuba’s armed forces. Suspecting an

antirevolutionary plot, Fidel Castro

had Mr. Matos arrested and charged

with treason.

Within two months, Mr. Matos was

tried, convicted and sentenced to 20

years in prison . When he was released

in 1979, Mr. Matos, nearly blind, went

into exile in the United States, where

he lived until his death in 2014.

Shortly after arriving in Miami and

joining the legions of Castro

opponents there, Mr. Matos told

Worldview magazine : “I differed from

Fidel Castro because the original

objective of our revolution was

‘Freedom or Death.’ Once Castro had

power, he began to kill freedom.”

It was not until just before the Bay of

Pigs invasion that Mr. Castro declared

publicly that his revolution was

socialist. A few months later, on Dec.

2, 1961, he removed any lingering

doubt about his loyalties when he

affirmed in a long speech, “I am a

Marxist-Leninist.”

Many Cubans who had willingly

accepted great sacrifice for what they

believed would be a democratic

revolution were dismayed. They broke

ranks with Mr. Castro, putting

themselves and their families at risk.

Others, from the safety of the United

States, publicly accused Mr. Castro of

betraying the revolution and called

him a tyrant. Even his family began to

raise doubts about his intentions.

“As I listened, I thought that surely he

must be a superb actor,” Mr. Castro’s

sister Juanita wrote in an account in

Life magazine in 1964, referring to

the December 1961 speech. “He had

fooled not only so many of his friends,

but his family as well.” She recalled

his upbringing as the son of a well-to-

do landowner in eastern Cuba who

had sent him to exclusive Jesuit

schools. In 1948, after Mr. Castro

married Mirta Díaz-Balart, whose

family had ties to the Batista

government, his father gave them a

three-month honeymoon in the United

States.

“How could Fidel, who had been given

the best of everything, be a

Communist?” Juanita Castro wrote.

“This was the riddle which paralyzed

me and so many other Cubans who

refused to believe that he was leading

our country into the Communist

camp.”

Although the young Fidel was deeply

involved in a radical student

movement at the University of

Havana, his early allegiance to

Communist doctrine was uncertain at

best. Some analysts believed that the

obstructionist attitudes of American

officials had pushed Mr. Castro toward

the Soviet Union.

Indeed, although Mr. Castro pursued

ideologically communist policies, he

never established a purely Communist

state in Cuba, nor did he adopt

orthodox Communist Party ideology.

Rather, what developed in Cuba was

less doctrinaire, a tropical form of

communism that suited his needs. He

centralized the economy and flattened

out much of the traditional hierarchy

of Cuban society, improving education

and health care for many Cubans,

while depriving them of free speech

and economic opportunity.

But unlike other Communist countries,

Cuba was never governed by a

functioning politburo; Mr. Castro

himself, and later his brother Rául,

filled all the important positions in the

party, the government and the army,

ruling Cuba as its maximum leader.

“The Cuban regime turns out to be

simply the case of a third-world

dictator seizing a useful ideology in

order to employ its wealth against his

enemies,” wrote the columnist Georgie

Anne Geyer, whose critical biography

of Mr. Castro was published in 1991.

In this view of Mr. Castro, he was

above all an old-style Spanish caudillo,

one of a long line of Latin American

strongmen who endeared themselves

to people searching for leaders. The

analyst Alvaro Vargas Llosa of the

Independent Institute in Washington

called him “the ultimate 20th-century

caudillo.”

In Cuba, through good times and bad,

Mr. Castro’s supporters referred to

themselves not as Communists but as

Fidelistas. He remained personally

popular among segments of Cuban

society even after his economic

policies created severe hardship. As

Mr. Castro consolidated power,

eliminated his enemies and grew

increasingly autocratic, the Cuban

people referred to him simply as Fidel.

To say “Castro” was considered

disloyal, although in later decades

Cubans would commonly say just that

and mean it. Or they would invoke his

overwhelming presence by simply

bringing a hand to their chins, as if to

stroke a beard.

Global Brinkmanship

Mr. Castro’s alignment with the Soviet

Union meant that the Cold War

between the world’s superpowers, and

the ideological battle between

democracy and communism, had

erupted in the United States’ sphere of

influence. A clash was all but

inevitable, and it came in October

1962 . American spy planes took

reconnaissance photos suggesting that

the Soviets had exploited their new

alliance to build bases in Cuba for

intermediate-range nuclear missiles

capable of reaching North America.

Mr. Castro allowed the bases to be

constructed, but once they were

discovered, he became a bit player in

the ensuing drama, overshadowed by

President John F. Kennedy and the

Soviet leader, Nikita S. Khrushchev.

Kennedy put United States military

forces on alert and ordered a naval

blockade of Cuba. The two sides were

at a stalemate for 13 tense days, and

the world held its breath.

Finally, after receiving assurances that

the United States would remove

American missiles from Turkey and

not invade Cuba, the Soviets withdrew

the missiles and dismantled the bases.

But the Soviet presence in Cuba

continued to grow. Soviet troops,

technicians and engineers streamed

in, eventually producing a generation

of blond Cubans with names like Yuri,

Alexi and Vladimiro. The Soviets were

willing to buy all the sugar Cuba could

produce. Even as other Caribbean

nations diversified, Cuba decided to

stick with one major crop, sugar, and

one major buyer.

But after forcing the entire nation

into a failed effort to reach a record

10-million-ton sugar harvest in 1970,

Mr. Castro recognized the need to

break the cycle of dependence on the

Soviets and sugar. Once more, he

relied on his belief in himself and his

revolution for solutions. One unlikely

consequence was his effort to develop

a Cuban supercow. Although he had

no training in animal husbandry, Mr.

Castro decided to crossbreed

humpbacked Asian Zebus with

standard Holsteins to create a new

breed that could produce milk at

prodigious rates.

Decades later, the Zebus could still be

found grazing in pastures across the

island, symbols of Mr. Castro’s

micromanagement. A few of the

hybrids did give more milk, and one

that set a milk production record was

stuffed and placed in a museum. But

most were no better producers than

their parents.

As the Soviets settled in Cuba in the

1960s, hundreds of Cuban students

were sent to Moscow, Prague and

other cities of the Soviet bloc to study

science and medicine. Admirers from

around the world, including some

Americans, were impressed with the

way that health care and literacy in

Cuba had improved. A reshaping of

Cuban society was underway.

Cuba’s tradition of racial segregation

was turned upside down as peasants

from the countryside, many of them

dark-skinned descendants of Africans

enslaved by the Spaniards centuries

before, were invited into Havana and

other cities that had been

overwhelmingly white. They were

given the keys to the elegant homes

and spacious apartments of the

middle-class Cubans who had fled to

the United States. Rents came to be

little more than symbolic, and basic

foods like milk and eggs were sold in

government stores at below

production cost.

Mr. Castro’s early overhauls also

changed Cuba in ways that were less

than utopian. Foreign-born priests

were exiled, and local clergy were

harassed so much that many closed

their churches. The Roman Catholic

Church excommunicated Mr. Castro

for violating a 1949 papal decree

against supporting Communism. He

established a sinister system of local

Committees for the Defense of the

Revolution, which set neighbors to

informing on neighbors. Thousands of

dissidents and homosexuals were

rounded up and sentenced to either

prison or forced labor. And although

blacks were welcomed into the cities,

Mr. Castro’s government remained

overwhelmingly white.

Mr. Castro regularly fanned the flames

of revolution with his oratory. In

marathon speeches, he incited the

Cuban people by laying out what he

considered the evils of capitalism in

general and of the United States in

particular. For decades, the regime

controlled all publications and

broadcasting outlets and restricted

access to goods and information in

ways that would not have been

possible if Cuba were not an island.

His revolution established at home,

Mr. Castro looked to export it.

Thousands of Cuban soldiers were

sent to Africa to fight in Angola ,

Mozambique and Ethiopia in support

of Communist insurgents. The strain

on Cuba’s treasury and its society was

immense, but Mr. Castro insisted on

being a global player in the

Communist struggle.

As potential threats to his rule were

eliminated, Mr. Castro tightened his

grip. Camilo Cienfuegos , who had led

a division in the insurrection and was

immensely popular in Cuba, was

killed in a plane crash days after

going to arrest Huber Matos in

Camagüey on Mr. Castro’s orders. His

body was never found. Che Guevara,

who had become hostile toward the

Soviet Union, broke with Mr. Castro

before going off to Bolivia, where he

was captured and killed in 1967 for

trying to incite a revolution there.

Despite the fiery rhetoric from Mr.

Castro in the early years of the

revolution, Washington did attempt a

reconciliation . By some accounts, in

the weeks before he was assassinated

in 1963, Kennedy had aides look at

mending fences, providing Mr. Castro

was willing to break with the Soviets.

But with Kennedy’s assassination, and

suspicions that Mr. Castro and the

Cubans were somehow involved, the

90 miles separating Cuba from the

United States became a gulf of

antagonism and mistrust. The C.I.A.

tried several times to eliminate Mr.

Castro or undermine his authority.

One plot involved exposing him to a

chemical that would cause his beard to

fall out, and another using a poison

pen to kill him. Mr. Castro often

boasted of how many times he had

escaped C.I.A. plots to kill him, and he

ordered information about the foiled

attempts to be put on display at a

Havana museum.

Relations between the United States

and Cuba briefly thawed in the 1970s

during the administration of President

Jimmy Carter. For the first time,

Cuban-Americans were allowed to

visit family in Havana under strict

guidelines. But that fleeting détente

ended in 1980 when Mr. Castro tried

to defuse growing domestic discontent

by allowing about 125,000 Cubans to

flee in boats, makeshift rafts and

inner tubes, departing from the beach

at Mariel. He used the opportunity to

empty Cuban prisons of criminals and

people with mental illnesses and force

them to join the Mariel boatlift. Mr.

Carter’s successor, Reagan, slammed

shut the door that Mr. Carter had

opened.

In 1989, when frustrated veterans

from Cuba’s African ventures began

rallying around Gen. Arnaldo Ochoa,

who led Cuban forces on the

continent, Mr. Castro effectively got

rid of a potential rival by bringing the

general and some of his supporters to

trial on drug charges. General Ochoa

and several other high-ranking

officers were executed on the orders

of Raúl Castro, who was then the

minister of defense.

The United States economic embargo,

imposed by Eisenhower and widened

by Kennedy, has continued for more

than five decades. But its effectiveness

was undermined by the Soviet Union,

which gave Cuba $5 billion a year in

subsidies, and later by Venezuela,

which sent Cuba badly needed oil and

long-term economic support. Most

other countries, including close United

States allies like Canada, maintained

relations with Cuba throughout the

decades and continued trading with

the island. In recent years, successive

American presidents have punched

big holes in the embargo, allowing a

broad range of economic activity,

though maintaining the ban on

tourism.

End of an Empire

“I faced my greatest challenge after I

turned 60,” Mr. Castro said in an

interview with Vanity Fair magazine

in 1994. He was referring to the

collapse of the Soviet empire, which

brought an end to the subsidies that

had kept his government afloat for so

long. He had also lost a steady source

of oil and a reliable buyer for Cuban

sugar.

Abandoned, isolated, facing increasing

dissent at home, Mr. Castro seemed to

have come to the end of his line.

Cuba’s collapse appeared imminent,

and Mr. Castro’s final hours in power

were widely anticipated. Miami exiles

began making elaborate preparations

for a triumphant return.

But Mr. Castro, defying predictions,

fought on. He chose an unlikely

weapon: the hated American dollar,

which he had long condemned as the

corrupt symbol of capitalism. In the

summer of 1993, he made it legal for

Cubans to hold American dollars spent

by tourists or sent by exiled family

members. That policy eventually led

to a dual currency system that has

fostered resentment and hampered

economic development in Cuba.

Mr. Castro, the self-proclaimed

Marxist-Leninist, was also willing to

experiment with capitalism and free

enterprise, at least for a time.

Encouraged by his brother Raúl, he

allowed farmers to sell excess produce

at market rates, and he ordered

officials to turn a blind eye to small,

family-run kitchens and restaurants,

called paladares, that charged market

prices. Under Rául Castro, those

reforms were broadened considerably,

though they were sometimes met with

public grumbling from his older

brother.

But despite his apparent distaste for

capitalism, and lingering memories of

the 1950s Cuba that preceded his rule,

Fidel Castro continued to foster Cuba’s

tourism industry. He allowed Spanish,

Italian and Canadian companies to

develop resort hotels and vacation

properties, usually in association with

an arm of the Cuban military.

For many years, the resorts were off

limits to most Cubans. They generated

hard cash, but a new generation of

struggling young Cuban women were

lured into prostitution by the tourists’

money.

For a time, Mexican and Canadian

investors poured money into the

decrepit telephone company (owned

by ITT until it was nationalized by Mr.

Castro in 1960), mining operations

and other enterprises, which helped

keep Cuba’s economy from collapsing.

He declared an emergency during

which he expected the Cuban people to

tighten their belts. He called the

United States embargo genocide.

All his efforts were not enough to keep

dissent from sprouting in Havana,

Santiago de Cuba and other urban

areas during this period of hardship.

Despite worldwide condemnation of

his actions, Mr. Castro clamped down

on a fledgling democracy movement,

jailing anyone who dared to call for

free elections. He also cracked down

on the nucleus of an independent

press, imprisoning or harassing Cuban

reporters and editors.

In 1994, for the first time,

demonstrators took to the streets of

Havana to express their anger over

the failed promises of the revolution.

Mr. Castro had to personally appeal

for calm. Then, in early 1996, he

seized an opportunity to rebuild his

support by again demonizing the

United States.

A South Florida group, Brothers to the

Rescue , had been flying three civilian

planes toward the Cuban coast when

two were shot down by Cuban military

jets. Four men on board were killed.

Mr. Castro raged against Washington,

maintaining that the planes had

violated Cuban airspace. American

officials condemned the attack.

Until then, President Bill Clinton had

been moving discreetly but steadily

toward easing the United States

embargo and re-establishing some

relations with Cuba. But in the wake

of the attack, and the virulent reaction

from Cuban-Americans in Florida — a

state Mr. Clinton considered important

to his re-election bid — he reluctantly

signed the Helms-Burton law , which

allowed the United States to punish

foreign companies that were using

confiscated American property in

Cuba.

The State Department’s first warnings

under the new law went to a

Canadian mining company that had

taken over a huge nickel mine, and a

Mexican investment group that had

purchased the Cuban telephone

company. Despite protests from

American allies, the United States

maintained the Helms-Burton law as a

weapon against Mr. Castro, although

all its provisions have never been

carried out.

But in Cuba, the American actions

reinforced Mr. Castro’s complaints

about American arrogance and helped

channel domestic dissent toward

Washington. One of his strengths as a

communicator — he considered

Reagan his only worthy competitor in

that regard — had always been to

transform his anger toward the United

States into a rallying cry for the Cuban

people.

“We are left with the honor of being

one of the few adversaries of the

United States,” Mr. Castro told Maria

Shriver of NBC in a 1998 interview.

When Ms. Shriver asked him if that

truly was an honor, he answered, “Of

course.”

“For such a small country as Cuba to

have such a gigantic country as the

United States live so obsessed with this

island,” he said, “it is an honor for

us.”

Parallel Lives

As he grew older and grayer, Mr.

Castro could no longer be easily linked

to the intense guerrilla fighter who

had come out of the Sierra Maestra.

He rambled incoherently in his long

speeches. He was rumored to be

suffering from various diseases. After

40 years, the revolution he started no

longer held promise, and Cubans by

the thousands, including many who

had never known any other life but

under Mr. Castro, risked their lives

trying to reach the United States on

rafts, inner tubes and even old trucks

outfitted with floats.

Although the revolution lost its luster,

what never diminished was Mr.

Castro’s ability to confound American

officials and to create situations to

seize the advantage of a particular

moment.

That was evident early in 1998 when

Pope John Paul II visited Havana and

met with Mr. Castro. The meeting was

widely expected to be seen as a rebuke

and an embarrassment to Mr. Castro.

The aging anti-Communist pontiff

stood beside the aging Communist

leader, who had abandoned his

military uniform for the occasion in

favor of a dark suit. The pope talked

about human rights and the lack of

basic freedoms in Cuba. But he also

called Washington’s embargo “unjust

and ethically unacceptable,” allowing

Mr. Castro to claim a political if not a

moral victory .

The next year, Mr. Castro converted

another conflict into an opportunity to

bolster his standing among his own

people while infuriating the United

States. A young woman and her 5-

year-old son were among more than a

dozen Cubans who had set out for

Florida in a 17-foot aluminum boat.

The boat capsized and the woman

drowned, but the boy, Elián González ,

survived two days in an inner tube

before being picked up by the United

States Coast Guard and taken to

Miami, where he was united with

relatives.

Later, however, the relatives refused

to release the boy when his father, in

Cuba, demanded his return. The

standoff between the family and

United States officials created the kind

of emotional and political drama that

Mr. Castro had become a master at

manipulating for his own purposes.

Mr. Castro made the boy another

symbol of American oppression, which

diverted attention from the

deteriorating conditions in Cuba.

After several months, American agents

seized the boy from his Miami

relatives and returned him to his

father in Cuba, where he was greeted

by Mr. Castro.

That episode carried great significance

for Mr. Castro in the way it echoed

one in his personal life.

Mr. Castro and his wife, Mirta Díaz-

Balart, divorced in 1955, six years

after the birth of their son, Fidelito.

In 1956, when Mr. Castro and Ms.

Díaz-Balart were both in Mexico, Mr.

Castro arranged to have the boy visit

him before embarking on what he

said would be a dangerous voyage,

which turned out to be his invasion of

Cuba. He promised to bring the boy

back in two weeks, but it was a trick.

At the end of that period, Mr. Castro

placed Fidelito in the custody of a

friend in Mexico City. He then sailed

for Cuba with his fellow rebels on the

yacht Granma.

The boy’s mother, with the help of her

family and the Cuban Embassy in

Mexico City, found a team of

professional kidnappers, who

ambushed the boy and his guardians

in a park and carried him off. Ms.

Díaz-Balart took Fidelito to New York

and enrolled him in a local school for

a year. But after Mr. Castro entered

Havana and grabbed control of the

government, he persuaded his former

wife to send the boy back. The

younger Mr. Castro lived in Cuba

until, years later, he was sent to the

Soviet Union to study. He became a

physicist, married a Russian woman

and eventually returned to Cuba,

where he was named head of Cuba’s

nuclear power program.

Details of Mr. Castro’s personal life

were always murky. He had no formal

home but lived in many different

houses and estates in and around

Havana. He had relationships with

several women, and only in his later

years was he willing to acknowledge

that he had a relationship of more

than 40 years with Dalia Soto del

Valle, who had rarely been seen in

public. (Whether they were legally

married was not clear.)

The two had five sons — Alexis,

Alexander, Alejandro, Antonio and

Ángel — all of whom live in Cuba. Mr.

Castro also has a daughter, Alina, a

radio host in Miami, who bitterly

attacked her father on the air for

years.

Mr. Castro had stormy relations with

many of his relatives both in Cuba and

the United States. He remained close

to Celia Sánchez, a woman who was

with him in the Sierra Maestra and

who looked after his schedule and his

archives devotedly, until she died in

1980. A sister, Ángela Castro, died at

88 in Havana in February 2012,

according to The Associated Press,

quoting her sister Juanita. And his

elder brother Ramón died in February

2016 at 91.

Outlasting all his enemies, Mr. Castro

lived to rule a country where the

overwhelming majority of people had

never known any other leader. Hardly

anyone talked openly of a time

without him until the day, in 2001,

when he appeared to faint while

giving a speech. Then, in 2004, he

stumbled while leaving a platform,

breaking a kneecap and reminding

Cubans again of his mortality and

forcing them to confront their future.

As Mr. Castro and his revolution aged,

Cuban dissidents grew bolder.

Oswaldo Payá , using a clause in the

Cuban Constitution, collected

thousands of signatures in a petition

demanding a referendum on free

speech and other political freedoms.

(Mr. Payá died in a car crash in 2012.)

Bloggers wrote disparagingly of Mr.

Castro and the regime, although most

of their missives could not be read in

Cuba, where internet access was

strictly limited.

A group of Cuban women who called

themselves the Ladies in White rallied

on Sundays to protest the

imprisonment of their fathers,

husbands and sons, whose pictures

they carried on posters inscribed with

the number of years to which they

were sentenced as political prisoners.

After being made his brother’s

successor, Raúl Castro tried to control

the fragments of the revolution that

remained after Fidel Castro fell ill,

including a close association with

President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela,

who modeled himself after Fidel. (Mr.

Chávez died in 2013.)

Never as popular as his brother, Raúl

Castro was considered a better

manager, and in some ways was seen

as more conscious of the everyday

needs of the Cuban people, despite his

reputation as the revolution’s

executioner. One of his first moves as

leader was to replace the grossly

overcrowded city buses, known as

“camels,” with new ones, many

imported from China. He opened up

the economy somewhat, allowing

entrepreneurs to start businesses, and

he eased restrictions on traveling,

access to cellphones, computers and

other personal items, and the buying

and selling of property.

Still, Raúl Castro came under

mounting pressure from Cubans

demanding even more economic and

political opportunity. He took more

steps to open the economy and, in so

doing, dismantled parts of the socialist

state that his brother had defended for

so long.

Lurking in the background as Raúl

Castro embarked on that new course

was the brooding visage of Fidel,

whose revolution has been seen as a

rebellion of one man. When President

Obama and Raúl Castro

simultaneously went on TV in their

countries in 2014 to announce a

prisoner exchange and the first steps

toward normalizing relations, Cubans

and Americans alike expected to hear

Fidel either accepting or condemning

the moves.

Six weeks after the deal was

announced, Mr. Castro, or someone

writing in his name, finally reacted in

a way that combined his own bluster

and his brother’s new approach.

“I do not trust the politics of the

United States, nor have I exchanged a

word with them, but this is not, in any

way, a rejection of a peaceful solution

to conflicts,” Mr. Castro wrote near

the end of a rambling letter to

students on the commemoration of the

70th anniversary of his own time at

the University of Havana.

Sounding more like his brother than

his old self, he backed any peaceful

attempts to resolve the problems

between the two countries. He then

took one final swipe at his old

nemesis.

“The grave dangers that threaten

humanity today have to give way to

norms that are compatible with

human dignity,” the letter said. “No

country is excluded from such rights.

With this spirit I have fought, and will

continue fighting, until my last

breath.”

In April 2016, a frail Mr. Castro made

what many thought would be his last

public appearance, at the Seventh

Congress of the Cuban Communist

Party. Dressed in an incongruous blue

tracksuit jacket, his hands at times

quivering and his once powerful voice

reduced to a tinny squawk, he

expressed surprise at having survived

to almost 90, and he bade farewell to

the party, the political system and the

revolutionary Cuba he had created.

“Soon I will be like everybody else,”

Mr. Castro said. “Our turn comes to us

all, but the ideas of Cuban communism

will endure.”

No one is sure if the force of the

revolution will dissipate without Mr.

Castro and, eventually, his brother.

But Fidel Castro’s impact on Latin

America and the Western Hemisphere

has the earmarks of lasting

indefinitely. The power of his

personality remains inescapable, for

better or worse, not only in Cuba but

also throughout Latin America.

“We are going to live with Fidel Castro

and all he stands for while he is

alive,” wrote Mr. Matthews of The

Times, whose own fortunes were

dimmed considerably by his

connection to Mr. Castro, “and with

his ghost when he is dead.”

the Western Hemisphere, bedeviled 11

American presidents and briefly

pushed the world to the brink of

nuclear war.

Fidel Castro, the fiery apostle of

revolution who brought the Cold War

to the Western Hemisphere in 1959

and then defied the United States for

nearly half a century as Cuba’s

maximum leader, bedeviling 11

American presidents and briefly

pushing the world to the brink of

nuclear war, died Friday. He was 90.

His death was announced by Cuban

state television.

In declining health for several years,

Mr. Castro had orchestrated what he

hoped would be the continuation of

his Communist revolution, stepping

aside in 2006 when he was felled by a

serious illness. He provisionally ceded

much of his power to his younger

brother Raúl, now 85, and two years

later formally resigned as president.

Raúl Castro, who had fought alongside

Fidel Castro from the earliest days of

the insurrection and remained

minister of defense and his brother’s

closest confidant, has ruled Cuba since

then, although he has told that the

Cuban people he intends to resign in

2018.

Fidel Castro had held on to power

longer than any other living national

leader except Queen Elizabeth II. He

became a towering international

figure whose importance in the 20th

century far exceeded what might have

been expected from the head of state

of a Caribbean island nation of 11

million people.

He dominated his country with

strength and symbolism from the day

he triumphantly entered Havana on

Jan. 8, 1959, and completed his

overthrow of Fulgencio Batista by

delivering his first major speech in the

capital before tens of thousands of

admirers at the vanquished dictator’s

military headquarters.

A spotlight shone on him as he

swaggered and spoke with passion

until dawn. Finally, white doves were

released to signal Cuba’s new peace.

When one landed on Mr. Castro,

perching on a shoulder, the crowd

erupted, chanting: “Fidel! Fidel!” To

the war-weary Cubans gathered there

and those watching on television, it

was an electrifying sign that their

young, bearded guerrilla leader was

destined to be their savior.

Most people in the crowd had no idea

what Mr. Castro planned for Cuba. A

master of image and myth, Mr. Castro

believed himself to be the messiah of

his fatherland, an indispensable force

with authority from on high to control

Cuba and its people.

He wielded power like a tyrant,

controlling every aspect of the island’s

existence. He was Cuba’s “Máximo

Lider.” From atop a Cuban Army tank,

he directed his country’s defense at

the Bay of Pigs. Countless details fell

to him, from selecting the color of

uniforms that Cuban soldiers wore in

Angola to overseeing a program to

produce a superbreed of milk cows.

He personally set the goals for sugar

harvests. He personally sent countless

men to prison.

ADVERTISEMENT

But it was more than repression and

fear that kept him and his totalitarian

government in power for so long. He

had both admirers and detractors in

Cuba and around the world. Some saw

him as a ruthless despot who trampled

rights and freedoms; many others

hailed him as the crowds did that first

night, as a revolutionary hero for the

ages.

Even when he fell ill and was

hospitalized with diverticulitis in the

summer of 2006, giving up most of his

powers for the first time, Mr. Castro

tried to dictate the details of his own

medical care and orchestrate the

continuation of his Communist

revolution, engaging a plan as old as

the revolution itself.

By handing power to his brother, Mr.

Castro once more raised the ire of his

enemies in Washington. United States

officials condemned the transition,

saying it prolonged a dictatorship and

again denied the long-suffering Cuban

people a chance to control their own

lives.

But in December 2014, President

Obama used his executive powers to

dial down the decades of antagonism

between Washington and Havana by

moving to exchange prisoners and

normalize diplomatic relations

between the two countries, a deal

worked out with the help of Pope

Francis and after 18 months of secret

talks between representatives of both

governments.

Though increasingly frail and rarely

seen in public, Mr. Castro even then

made clear his enduring mistrust of

the United States. A few days after Mr.

Obama’s highly publicized visit to

Cuba in 2016 — the first by a sitting

American president in 88 years — Mr.

Castro penned a cranky response

denigrating Mr. Obama’s overtures of

peace and insisting that Cuba did not

need anything the United States was

offering.

To many, Fidel Castro was a self-

obsessed zealot whose belief in his

own destiny was unshakable, a

chameleon whose economic and

political colors were determined more

by pragmatism than by doctrine. But

in his chest beat the heart of a true

rebel. “Fidel Castro,” said Henry M.

Wriston , the president of the Council

on Foreign Relations in the 1950s and

early ’60s, “was everything a

revolutionary should be.”

Mr. Castro was perhaps the most

important leader to emerge from

Latin America since the wars of

independence in the early 19th

century. He was decidedly the most

influential shaper of Cuban history

since his own hero, José Martí ,

struggled for Cuban independence in

the late 19th century. Mr. Castro’s

revolution transformed Cuban society

and had a longer-lasting impact

throughout the region than that of any

other 20th-century Latin American

insurrection, with the possible

exception of the 1910 Mexican

Revolution .

His legacy in Cuba and elsewhere has

been a mixed record of social progress

and abject poverty, of racial equality

and political persecution, of medical

advances and a degree of misery

comparable to the conditions that

existed in Cuba when he entered

Havana as a victorious guerrilla

commander in 1959.

That image made him a symbol of

revolution throughout the world and

an inspiration to many imitators.

Hugo Chávez of Venezuela considered

Mr. Castro his ideological godfather.

Subcommander Marcos began a revolt

in the mountains of southern Mexico

in 1994, using many of the same

tactics. Even Mr. Castro’s spotty

performance as an aging autocrat in

charge of a foundering economy could

not undermine his image.

But beyond anything else, it was Mr.

Castro’s obsession with the United

States, and America’s obsession with

him, that shaped his rule. After he

embraced Communism, Washington

portrayed him as a devil and a tyrant

and repeatedly tried to remove him

from power through an ill-fated

invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, an

economic embargo that has lasted

decades, assassination plots and even

bizarre plans to undercut his prestige

by making his beard fall out.

Mr. Castro’s defiance of American

power made him a beacon of

resistance in Latin America and

elsewhere, and his bushy beard, long

Cuban cigar and green fatigues

became universal symbols of

rebellion.

Mr. Castro’s understanding of the

power of images, especially on

television, helped him retain the

loyalty of many Cubans even during

the harshest periods of deprivation

and isolation when he routinely

blamed America and its embargo for

many of Cuba’s ills. And his mastery

of words in thousands of speeches,

often lasting hours, imbued many

Cubans with his own hatred of the

United States by keeping them on

constant watch for an invasion —

military, economic or ideological —

from the north.

Over many years Mr. Castro gave

hundreds of interviews and retained

the ability to twist the most

compromising question to his favor.

In a 1985 interview in Playboy

magazine, he was asked how he would

respond to President Ronald Reagan’s

description of him as a ruthless

military dictator. “Let’s think about

your question,” Mr. Castro said, toying

with his interviewer. “If being a

dictator means governing by decree,

then you might use that argument to

accuse the pope of being a dictator.”

He turned the question back on

Reagan: “If his power includes

something as monstrously

undemocratic as the ability to order a

thermonuclear war, I ask you, who

then is more of a dictator, the

president of the United States or I?”

ADVERTISEMENT

After leading his guerrillas against a

repressive Cuban dictator, Mr. Castro,

in his early 30s, aligned Cuba with the

Soviet Union and used Cuban troops

to support revolution in Africa and

throughout Latin America.

His willingness to allow the Soviets to

build missile-launching sites in Cuba

led to a harrowing diplomatic standoff

between the United States and the

Soviet Union in the fall of 1962, one

that could have escalated into a

nuclear exchange. The world

remained tense until the

confrontation was defused 13 days

after it began, and the launching pads

were dismantled.

With the dissolution of the Soviet

Union in 1991, Mr. Castro faced one of

his biggest challenges: surviving

without huge Communist subsidies. He

defied predictions of his political

demise. When threatened, he fanned

antagonism toward the United States.

And when the Cuban economy neared

collapse, he legalized the United States

dollar , which he had railed against

since the 1950s, only to ban dollars

again a few years later when the

economy stabilized.

Mr. Castro continued to taunt

American presidents for a half-

century, frustrating all of

Washington’s attempts to contain him.

After nearly five decades as a pariah

of the West, even when his once

booming voice had withered to an old

man’s whisper and his beard had

turned gray, he remained defiant.

He often told interviewers that he

identified with Don Quixote, and like

Quixote he struggled against threats

both real and imagined, preparing for

decades, for example, for another

invasion that never came. As the

leaders of every other nation of the

hemisphere gathered in Quebec City in

April 2001 for the third Summit of the

Americas , an uninvited Mr. Castro,

then 74, fumed in Havana, presiding

over ceremonies commemorating the

embarrassing defeat of C.I.A.-backed

exiles at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. True

to character, he portrayed his

exclusion as a sign of strength,

declaring that Cuba “is the only

country in the world that does not

need to trade with the United States.”

Personal Powers

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz was born

on Aug. 13, 1926 — 1927 in some

reports — in what was then the

eastern Cuban province of Oriente, the

son of a plantation owner, Ángel

Castro, and one of his maids, Lina Ruz

González , who became his second wife

and had seven children. The father

was a Spaniard who had arrived in

Cuba under mysterious circumstances.

One account, supported by Mr. Castro

himself, was that his father had agreed

to take the place of a Spanish

aristocrat who had been drafted into

the Spanish Army in the late 19th

century to fight against Cuban

independence and American

hegemony.

Other versions suggest that Ángel

Castro went penniless to Cuba but

eventually established a plantation

and did business with the despised,

American-owned United Fruit

Company. By the time Fidel was a

youngster, his father was a major

landholder.

Fidel was a boisterous young student

who was sent away to study with the

Jesuits at the Colegio de Dolores in

Santiago de Cuba and later to the

Colegio de Belén, an exclusive Jesuit

high school in Havana. Cuban lore has

it that he was headstrong and

fanatical even as a boy. In one

account, Fidel was said to have

bicycled head-on into a wall to make a

point to his friends about the strength

of his will.

In another often-repeated tale, young

Fidel and his class were led on a

mountain hike by a priest. The priest

slipped in a fast-moving stream and

was in danger of drowning until Fidel

pulled him to shore, then both knelt in

prayers of thanks for their good

fortune.

A sense of destiny accompanied Mr.

Castro as he entered the University of

Havana’s law school in 1945 and

almost immediately immersed himself

in radical politics. He took part in an

invasion of the Dominican Republic

that unsuccessfully tried to oust the

dictator Rafael Trujillo. He became

increasingly obsessed with Cuban

politics and led student protests and

demonstrations even when he was not

enrolled in the university.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mr. Castro’s university days earned

him the image of rabble-rouser and

seemed to support the view that he

had had Communist leanings all along.

But in an interview in 1981, quoted in

Tad Szulc’s 1986 biography, “ Fidel ,”

Mr. Castro said that he had flirted

with Communist ideas but did not join

the party.

“I had entered into contact with

Marxist literature,” Mr. Castro said.

“At that time, there were some

Communist students at the University

of Havana, and I had friendly

relations with them, but I was not in

the Socialist Youth, I was not a

militant in the Communist Party.”

He acknowledged that radical

philosophy had influenced his

character: “I was then acquiring a

revolutionary conscience; I was active;

I struggled, but let us say I was an

independent fighter.”

After receiving his law degree, Mr.

Castro briefly represented the poor,

often bartering his services for food.

In 1952, he ran for Congress as a

candidate for the opposition Orthodox

Party. But the election was scuttled

because of a coup staged by Mr.

Batista.

Mr. Castro’s initial response to the

Batista government was to challenge it

with a legal appeal, claiming that Mr.

Batista’s actions had violated the

Constitution. Even as a symbolic act,

the attempt was futile.

His core group of radical students

gained followers, and on July 26,

1953 , Mr. Castro led them in an attack

on the Moncada barracks in Santiago

de Cuba. Many of the rebels were

killed. The others were captured, as

were Mr. Castro and his brother Raúl.

At his trial, Mr. Castro defended the

attack. Mr. Batista had issued an

order not to discuss the proceedings,

but six Cuban journalists who had

been allowed in the courtroom

recorded Mr. Castro’s defense.

“As for me, I know that jail will be as

hard as it has ever been for anyone,

filled with threats, with vileness and

cowardly brutality,” Mr. Castro

declared . “I do not fear this, as I do

not fear the fury of the miserable

tyrant who snuffed out the life of 70

brothers of mine. Condemn me, it does

not matter. History will absolve me.”

Mr. Castro was sentenced to 15 years

in prison. Mr. Batista then made what

turned out to be a huge strategic

error. Believing that the rebels’ energy

had been spent, and under pressure

from civic leaders to show that he was

not a dictator, he released Mr. Castro

and his followers in an amnesty after

the 1954 presidential election.

Mr. Castro went into exile in Mexico,

where he plotted his return to Cuba.

He tried to buy a used American PT

boat to carry his band to Cuba, but the

deal fell through. Then he caught sight

of a beat-up 61-foot wooden yacht

named Granma, once owned by an

American who lived in Mexico City.

The Granma remains on display in

Havana, encased in glass.

Man of the Mountains

During Mr. Castro’s long rule, his

character and image underwent

several transformations, beginning

with his days as a revolutionary in the

Sierra Maestra of eastern Cuba. After

arriving on the coast in the

overloaded yacht with Che Guevara

and 80 of their comrades in December

1956, Mr. Castro took on the role of

freedom fighter. He engaged in a

campaign of harassment and guerrilla

warfare that infuriated Mr. Batista,

who had seized power in a 1952

garrison revolt, ending a brief period

of democracy.

Although his soldiers and weapons

vastly outnumbered Mr. Castro’s, Mr.

Batista grew fearful of the young

guerrilla’s mesmerizing oratory. He

ordered government troops not to rest

until they had killed Mr. Castro, and

the army frequently reported that it

had done so. Newspapers around the

world reported his death in the

December 1956 landing. But three

months later, Mr. Castro was

interviewed for a series of articles that

would revive his movement and thus

change history.

The escapade began when Castro

loyalists contacted a correspondent

and editorial writer for The New York

Times, Herbert L. Matthews, and

arranged for him to interview Mr.

Castro. A few Castro supporters took

Mr. Matthews into the mountains

disguised as a wealthy American

planter.

ADVERTISEMENT

Drawing on his reporting, Mr.

Matthews wrote sympathetically of

both the man and his movement,

describing Mr. Castro, then 30, parting

the jungle leaves and striding into a

clearing for the interview.

“This was quite a man — a powerful

six-footer, olive-skinned, full-faced,

with a straggly beard,” Mr. Matthews

wrote.

The three articles, which began in The

Times on Sunday, Feb. 24, 1957,

presented a Castro that Americans

could root for. “The personality of the

man is overpowering,” Mr. Matthews

wrote. “Here was an educated,

dedicated fanatic, a man of ideals, of

courage and of remarkable qualities of

leadership.”

The articles repeated Mr. Castro’s

assertions that Cuba’s future was

anything but a Communist state. “He

has strong ideas of liberty, democracy,

social justice, the need to restore the

Constitution, to hold elections,” Mr.

Matthews wrote. When asked about

the United States, Mr. Castro replied,

“You can be sure we have no

animosity toward the United States

and the American people.”

The Cuban government denounced Mr.

Matthews and called the articles

fabrications. But the news that he had

survived the landing breathed life into

Mr. Castro’s movement. His small

band of irregulars skirmished with

government troops, and each

encounter increased their support in

Cuba and around the world, even

though other insurgent forces in the

cities were also fighting to overthrow

the Batista government.

It was the symbolic strength of his

movement, not the armaments under

Mr. Castro’s control, that

overwhelmed the government. By the

time Mr. Batista fled from a darkened

Havana airport just after midnight on